Oh, Hi again!

One thing I think about a bit is what sort of language speaks and writes the world we live in now. Yes, I do know that language is signification—words are signs signifying things in the world. But sometimes words fail, right, to reflect or signify? Like the word Genocide? Does it really describe or capture what it signifies? Or Capital? Or Slavery? Or words like Mass Grave? Or Child Prostitution?

I mean, what do you SEE when you READ these words? And is what you see true to what they signify? Another good way of saying this is to talk about what queer visual theorist Diana Taylor calls “percepticide,” an act of “making what was so obviously visible … seemingly invisible to the audience and resistant to a critique.

Can language truly signify atrocity? Like Israel’s genocide in Palestine? Or is it compelled to enact percepticide when faced with what exceeds, overwhelms, blood-spatters, its signifying aperture?

So on this issue I want to share with you today some pretty damn spot on words by a brilliant writer that I just came across. His name is Omar El Akkad, and his topic is “How the Empire Weaponizes Language to Numb Itself to Genocide.” His new non-fiction book, One Day Everyone Will Have Always Been Against This, captures exactly the sometimes hollow heart of language I’ve described above.

You can read the whole interview of Ekkad by Bareerah Ghani here.

But some pertinent words are as follows:

“if you presented plainly, both in imagery and in language, the reality of not just what is happening in Gaza, but what is happening in the West Bank, and what has been happening to Palestinians for the better part of three quarters of a century, even the most well versed in looking away would have trouble digesting it. But under the guise of language that describes an entire population as being a terrorist entity, for example, or uses passive language to describe a bullet colliding with a 4-year-old young lady—I could not for the life of me tell you what a 4-year-old young lady is—you can cocoon it, and you can soften it, and you can bubble wrap it . . . . The kind of person I’m thinking of with that title [One Day Everyone Will Have Been Against This] is the kind of person for whom none of this matters. There’s no personal stakes. They can’t point out Israel or Palestine on a map. They simply want to know what the majority of polite society is thinking right now. There is this narrative that sort of appears well after the fact, where the horrible thing is considered this temporary aberration. They didn’t know better back then. Now we know better. It’s never true. It wasn’t true in the case of slavery or segregation or apartheid, and it won’t be true in this situation. It’ll just be an effective and useful narrative parachute . . . . In that context, I think that all of us as writers have an obligation, first and foremost, to bear witness, even if we knew for a fact that it wouldn’t change a single thing. . . . . For example, the War on Terror, where there were these periods of immense silence, so many artists, so many writers kept their heads down and then you started to see, when it was safe enough, a trickle of stories after the fact, usually from the perspective of some former marine talking about how sad it made them to have to kill all these brown folks, and then their short story collection wins whatever prestigious prize. To know that this arc is likely still available to all of those writers where, 23 years from now, the same people who said nothing, are going to write incredibly moving stories about the mass graves they uncover in Northern Gaza, is infuriating. . . . Palestine is going to be free, and beyond that it is going to teach generations of human beings about what freedom actually looks like. And this work is going to be aided by activists around the world but is going to be done, and is being done by Palestinians themselves.”

Lots, lots to think about, especially if you are a writer thinking about writing something to refuse percepticide.

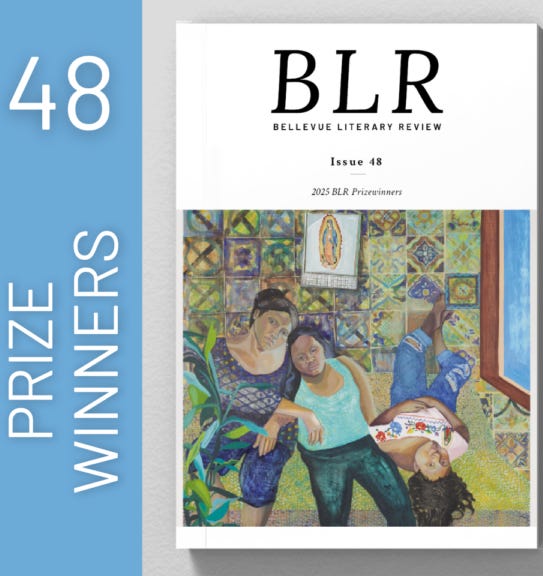

I’ll end with a little effort of my own at anti-percepticide. I describe what follows as narrating bearing witness, both by my character and by my author persona. It’s an excerpt from my short story “Gurung’s Women.” It just came out in the ever-marvelous Bellevue Literary Review, a literary journal that I’ve bowed down to and worshipped as a reader and trainee writer, and finding myself in whose pages is a dream come true about trying to make words do the work of at least mitigating harm if they cannot quite heal personal and collective historic wounds.

Because, “all of us as writers have an obligation, first and foremost, to bear witness, even if we knew for a fact that it wouldn’t change a single thing.” At least, we at least have that obligation.

Gurung’s Women, from BLR Issue 48, April 2025

The Nepali servant Gurung sweeps the floors and empties ashtrays in exhausted resignation. Rich memsaabs in city homes smoke, he knows, but this memsaab’s home—his Memsaab’s home—is something else. “Does every woman in this household smoke?” he asks out loud, as if compelled to ask this question, not just a personal question but one dictated by the cosmos, not just by his own cosmos as a poor man’s rented-out son, but by all of man’s reign over earth, by man’s eternal shock at the things women will get up to if not watched, which is why, they say, manly gods have routinely appeared in every age, divinely ordained, to save mankind from kaliyug, the end of times. Also, ultimately, compelled by Gurung’s worries about Memsaab’s niggling dry cough. And, by his helplessness.

Because Memsaab, the lady of the house, her husband absent for work in foreign lands, is an absolute queen. It’s her blinding beauty, of course, but also her manner, her stance. Distant, commanding. Her beauty itself seems to bore her. She will openly dig her nose and her morning-crusty eyes in front of people as if how can her spell possibly break, no matter what. Walks on air. The scruffy bell-bottomed, lush-whiskered young men who visit nightly—kinsmen, her brothers-in-law, he knows, but still—are clearly all helplessly in awe of and protectively in love with her. The second condition too, Gurung knows, he might have found himself in, being only nineteen, if he hadn’t grown up with a father who considered it his divinely ordained manly duty to come home nightly and lash some sense into wife and children at the end of a belt improvised from cowhide fastening that dropped with all the ferocity of a cat o’ nine tails on skin already chafed from hunger and winter.

Maybe he’d feel awe but not protective about Memsaab if his father’s belt hadn’t regularly dropped on his mother. Or if that mother whom eleven-year-old Gurung couldn’t shield from the belt had stayed. But she didn’t.

All night the kinsmen sit up—almost all night, but Gurung is needfully, heavily asleep far before they ever hit the guest khatiyas on the attached terrace balcony outside, or the razais and chatais on the floors of the rooms other than Memsaab’s bedroom—and smoke and drink tea and play cards and sometimes ask one of Memsaab’s visiting female cousins to sing Bollywood song favorites. Once Memsaab is done, though, she throws all the men out of her bedroom, however they might protest, and sleeps alone or with her cousins. And of course, when the master Saab returns from foreign parts where he works, with him.

And Saab is a very important Afsar working in some important big factory “in foreign,” and Gurung both tries to catch his eye and doesn’t. He would like to catch Saab’s eye so that in case there’s a better, more manly job in Saab’s factory “in foreign,” Saab would see him and think, “Oh, here’s a good man I can take with me to foreign,” and then two birds, one stone. The reason he doesn’t want to catch Saab’s eye is that Saab scares him. He has large bloodshot eyes. Over six feet tall, broad-shouldered like a wrestler. At night, when Saab goes to sleep with Memsaab in her bedroom—all-night card and tea parties all stopped now, the men, kin, coming only in the evening, sitting obediently and quietly on the sofa in front of Saab, their big brother, drinking only one, maximum two, cups of tea, making, thank God, less work for Gurung, slinking away after supper—Gurung can sometimes hear sounds from inside. And once he has heard a loud, angry man’s voice say “Whore!” He couldn’t have imagined such a thing would happen, and still has trouble believing, but he did hear.

“Whore” is a word Gurung has often heard before. When his mother still lived with him, his four sisters and two brothers, and his father, in the hills, in their family shack that always had at least one or two walls needing tarp reinforcement, though the rest of the tarp anyway never kept out the snow and the freezing drafts though his father said—insisted—it could.

“Whore!” his father shouted many days when he returned home blind drunk to find Gurung’s mother gone from the tattered shack, Gurung’s oldest sister and Gurung himself quickly, anxiously stirring gruel of some kind, any kind, on the sputtering, crumpled clay heap they called “oven” in a corner, so maybe, maybe, father’s rage would lose the battle against father’s growling stomach and then stomach, satisfied, would quickly recruit heart, liver, pancreas, brain, and eyes into a dead faint of a sleep at whose end, maybe late next morning, mother would be back, and then father’s wrath would either fall on her, or he would have forgotten, or not bother, since she was back, since she left all the time anyway.

Which Memsaab of course wouldn’t do, even if the word “whore” was heard one night. Because Memsaab commands with beauty; Gurung has seen even Saab follow her with eyes bloodshot but soft.

But the last time his mother left, that evening, Gurung’s father had roared “whore!” in a tone and with a loudness that had twisted all their guts—those brothers, sisters, that Gurung tried to herd away, hide at such times—that he’d never heard before, that he hoped never to hear again, so quickly it had sent all the blood from his body back into his pumping, nearly exploding heart. That was the time his mother never came back.

It’s hard for him to understand why Saab would use that word. Memsaab isn’t, can never be, a whore. It’s impossible, she rules the house, the brothers-in-law, the other guests, and even the neighborhood, with the hard scepter of her gaze, the blazing solar flare of her cold beauty. He only noticed that the next morning Saab’s eyes were red but soft again, Memsaab’s the same great bottomless pools. . . . .”

Till soon . . . . And if you’d like me to share more with you . . . .