Railways? Or freedom? What Can Indian Women Really Have?

The RG Kar case, Sati, Draupadi, Women in Politics, and Politics aroundWomen

Railways? Or freedom? What Can Indian Women Really Have?

If you don’t live in India and haven’t heard about this case, this young trainee doctor was raped and murdered brutally on 9 August 2024 in one of India’s oldest teaching hospitals, the R. G. Kar hospital. The murder was then pinned on “Sanjay Roy,” miniscule fry in the local lagoon of networked blue and white-collar crime but helpfully a known petty criminal and womanizer.

On January 20, the Sealdah Civil and Criminal Court sentenced Sanjay Roy, to life imprisonment in the case. The possible real architects of this monstrous murder, including the college principal Sandip Ghosh who masterminded many illegal and corrupt rackets run on campus, were cleared of the charge of brutalizing and murdering Moumita Debnath, who, some say, threatened to blow the whistle on the campus rackets.

Nobody believes justice was done in this case or ever will be. The results demonstrate, again, that Indian women and their bodies have long been and remain nothing but ciphers in men’s bids for power. Let me say why I think so.

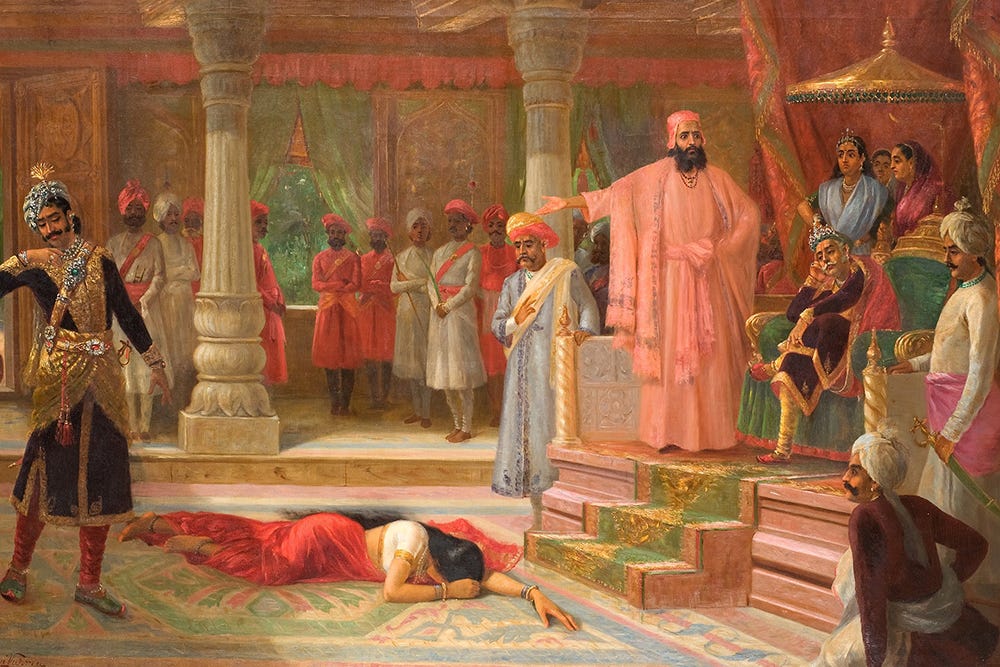

First, staging male power struggles on women’s bodies begins in India at least with Draupadi's public near-disrobing in the fourth-century epic Mahabharata. Here’s the scenario—Draupadi, a queen, is gambled away by her husband king Yudhishthira (considered exemplary in wisdom and virtue among men but fatally addicted to gambling) in a game. Only the gods can save her, and Lord Krishna did by adding unlimited length to her sari.

No god came to save Moumita Debnath.

Second, to show how Indian (and other) women “remain” ciphers in male power contests, we might look at the history of the abolition of Sati, a massive collective violence against women in precolonial and colonial India involving widows burned alive on their husbands’ funeral pyres. Comparing the R G Kar hospital rape and murder case and the abolition of Sati in colonial India may seem like a long shot. But here’s the story. It’s a convoluted history, so bear with me.

Hindu men and priests swore Sati was voluntary. They claimed pious Hindu women wanted to accompany their dead husbands to the afterlife rather than survive them. Supposedly they were free agents, these devout Hindu wives.

Ironically, given the known cruelty toward living Indian widows even today, widely reported in literature and film, such a choice might actually have even made a kind of ghoulish sense.

But the real reason for Sati was to kill off women who might become claimants of property, economic burdens and threatening unclaimed sexual bodies. Deepa Mehta’s film Water is a must-see on this, and Tagore’s Chokher Bali a must-read.

In colonial times, Sati became the center of a well-known maelstrom between Indians and British colonizers. The British said it was a barbaric custom needing to be uprooted if India was to be a civilized country. And in 1829, Governor-General Lord Bentick abolished Sati after “consulting” with male religious leaders, scriptural experts, as well as influential reformist Indian “Rajahs” such as Ram Mohan Roy.

Sounds terrific, doesn’t it? Especially for those poor, helpless Indian women? The British look really good in that light too—what a scholar has called “White women saving brown women from brown men.” Bentinck prpbably thought he looked downright noble, right?

More power to him and native reformers of Hindu society?

Nope. Rule Britannia was indifferent to real Indian women’s real bodies and soul. As Lata Mani impressively showed in her book Contentious Traditions, the debate on Sati in Bengal and Britain between 1780 and 1833 was among East India Company officials, Hindu pundits (scholars), Bengali bhadralok (men of the urban and upper-caste "respectable" class), munshis (teachers), Christian missionaries, and members of Parliament, among others. Mani doesn’t defend Sati, of course, or argue that the British should have let it go on. She simply proves beyond doubt that its “contended” ground was a male arena of debate for male power-sharing, even if unequally.

And who lay buried under this mass of male (native) learning and (British) power? The Indian women resonantly silent until their bodies were on fire, or, if “saved by white men,” living lives of social death, poor, ghettoized, ostracized, and often sexually exploited.

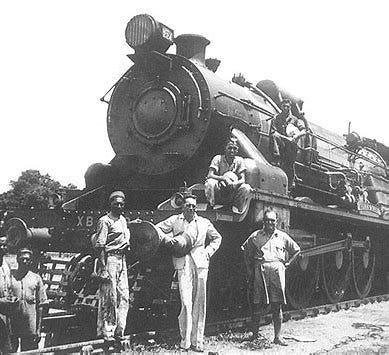

Regrettably, seeing white men were as enlightened altruistic saviors of their Indian subjects rather than winners of an ideological gamble didn’t die out in free India. Allow me to tell you about my grandfather, now deceased, who’d often say that at least during British rule of India there was law and order, the streets were safe, and trains would run on time.

Sad brainwashed poppycock, I know. The British didn’t at all bring the railways to India for the Indians’ convenience and advancement, but their own. The streets were safe, or safer, maybe, but only for them and for those Indians who did not defy British rule—reformer Ram Mohan Roy acquired his money and clout in the first place as a business “asset,” a comprador agent for the British—and not for those who defined colonial law and order or became freedom fighters.

My grandfather was deaf to such opposition and inconsolable about independent India’s disarray. Further, he contended that India’s independence only brought India chaos through the rule of the worst sort of Indian lumpen.

And this is the dangerous crossroads of deciding on what Indian women are allowed to have where many Indians stand today, as the R G Kar case substantiates. Details: a young postgraduate medical doctor was brutally raped and murdered—more ghoulish accounts say murdered and then raped—in a respected government hospital while a on break. Soon, increasingly unbelievable things came to light, such as the principal Sandip Ghosh tampering with evidence to remove traces of his associates’ involvement. Ghosh was said to be a known ally and “asset” of the formidable woman chief minister, Mamata Banerjee, thus having political immunity of sorts. Banerjee is perceived to be in cahoots with other such janissaries among the ranks of her party, some of whom have been responsible but not indicted for both well-known public and private acts of gender violence and intimidation. The handprints of my grandfather’s “worst sort of lumpen” were all over the place and the atrocity. The case was then transferred from the police to the Central Bureau of Investigation by the Kolkata High Court order on accusations of coverups and procedural violations.

The immense mass affect and public protests that followed in Kolkata—and other cities—can be compared in some ways to historic nationalist marches for Indian independence from British occupation. Where was the safety for women? Where was justice for women? These were the cries and calls of the protesters.

And at that point I heard educated people I respect express opinions and proffer solutions like my grandfather’s, partly as a horrified reaction to this case.

How?

The event seems structurally related to misrule by a powerful woman. A regime, it’s bruited about, in which women are not safe under the rule of a woman who calls herself “Didi,” or “elder sister” of her people. Megha Majumdar’s beautiful novel A Burning allegorically chronicles many perceptions of this regime and its female leader. The marginalization of women as subjects—and always already only the turf of patriarchal polo and wars—was once more the political tragicomedy that played in India as Mamata Banerjee became the face of the West Bengal “necro-state,” and Moumita Debnath lay dead.

The general outrage led to demands for Mamata Banerjee’s removal from her position and the imposition of President’s rule. But where did the loudest call emerge for the dismissal of Mamata Banerjee and President’s rule in her state? From none other than the at least equally morally bankrupt ultranationalist, male chauvinist, ethnocidal Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) government ruling the country, with party top brass Narendra Modi as prime minister. Mamata, or “Didi”—meaning elder sister—is no saint. But she certainly is a thorn in the side of Modi whose rule has made the entire nation necrotic for women. Both her “brand” image and the opposition to it inside and outside West Bengal are nothing if not gendered, boiling down to what kind of “woman” this leader is. On the other hand, Narendra Modi doesn’t exactly have a women-centric, gender justice track record. Nicknamed the “Butcher of Gujarat” for standing by as chief minister during an infamous pogrom of Muslims in his home state of Gujarat during which Muslim men were slaughtered and Muslim women were raped and disemboweled in full public view—he’s said to have instructed the police to do nothing to help the victims—he still wins election after election as Prime Minister of India.

I have no truck with butchers in general, being vegetarian, but it seems that politically focused violence and intimidation as a standing mechanism for control distinguish Modi’s government. Some of the violence is symbolic and spectacular, such as the Gujarat pogrom. But on a routine and regular basis, the BJP party shows its true colors by targeting minority communities such as Muslims, Christians, and Dalits for violence and intimidation. Since a main argument in this blog is that violence is structural, let me not forget to cite the structural basis for “lumpen” pogroms against minorities in the BJP’s history. The BJP formed out of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), one of whose members, Nathuram Godse, assassinated Mahatma Gandhi as vengeance for his perceived softness toward minorities. Thus, not only women and Muslims, but even the “Father of the Nation,” Bapu, was not safe from Hindu fundamentalist nationalists.

If the BJP makes the streets in any way safe for women under its rule, its corollary is the myth that Bentinck abolished Sati to save brown women from brown men. The BJP’s religious warriors—the RSS and the Bajrang Dal—have distinguished themselves as an army of thugs and goons searching out more Muslims for casual everyday butchery. Everyone knows this. Many have witnessed it and kept quiet out of fear or subtle assent. Though rich Indian Hindus in the diaspora do adore Modi and fund his coffers. Keeps him going nicely.

To carry on with the RG Kar event, though, countervoices emerged upon the BJP’s demand for President’s rule in West Bengal. They argued that such pressure was nothing but a BJP/Modi ploy to remove the biggest, most obdurate obstacle to the BJP’s recapture of West Bengal. Which made Mamata Banerjee a target for overwhelmingly male political marksmanship.

If my grandfather had he been around I might have asked him if he thought the British would have stopped, if they were still ruling India, the “lumpen” Modi pogroms, saving Muslim women and men. The true answer is “No.” Why? Because the British contributed handily and mightily to Hindu-Muslim hatred during their rule of India. Indeed, this was their cornerstone “Divide and Conquer” policy, which strengthened only their own hand and weakened that of all Indians, Hindu or Muslim, eventually leading to the genocidal Partition of India and Pakistan during which hundreds of thousands of women were raped and murdered. (How history repeats.) The British did exactly nothing to stop that.

And who did the British invite into their chambers and conference rooms where the murder and rape of women during Partition was signed off on? Why, the descendants of Ram Mohun Roy himself, the British-trained lawyers leading the Congress and the Muslim League, who collaborated and cooperated with their soon-to-be former masters without consulting the woman—or man—on the Indian street. A gentlemen’s handshake over genocide and feminicide.

Railways, or Freedom?

Do you see the parallels between the R G Kar case, Sati, and the (attempted) disrobing of Draupadi now? And perhaps even with the demonizing and scapegoating of East Bengal’s not especially savory female chief minister Mamata Banerjee? I hope you do. The political repercussions of the R G Kar case for West Bengal’s female chief minister indicate a wider male hegemonic structure wherein one woman’s desecration compensates for another woman’s destruction. Women's agency is sacrificed, while their bodies become ciphers in patriarchal power struggles.

So do Indian women always have to choose between being well policed and being free? Must they be selectively “protected” by lumpen warlords, or speak and act as free agents unprotected by those elected to do so? Why are rule of law and freedom together out of the question?

That conundrum establishes that women and their bodies have long been nothing but fungibles and ciphers and in men’s bids for power. They have been the stages on which male political epics have been enacted, beginning with the public disrobing of Draupadi in the Mahabharata. These are instances of a largely male hegemonic structure proposing one female body’s desecration as recompense for another woman’s destruction. What gets lost in the exchange is not whether West Bengal’s chief minister Mamata Banerjee is better or worse than Narendra Modi. The question is why and how women remain ciphers in male games of political chess.

The answer, I believe, is that both in colonial and postcolonial India, the Lords remain male, the Flies remain female, and are killed for the sport of the Lords. My grandfather was wrong in not seeing the Railways and civic order in British India as amenities only for those who shouldered “The White Man’s Burden,” not for the Burdens themselves. But he may have been right about the “worst sort of lumpen” part. Post-independence hard right nativist Hindu fundamentalist neonationalism thrusting up against regional revolts led by also unsavory false idols with clay feet seems to present only impossible choices for Indian women yet again. And in the chambers and corridors of power of those edifices, top of no one’s mind is the actual wellbeing, safety, freedom, or agency of Indian women.

How long will Indian women have to choose between Railways and freedom?

A scathing analysis of the evils perpetrated by colonial and indigenous patriarchy against Indian women. A much needed analysis that contextualizes the brutal rape and murder of Dr. Debnath.